酒精

簡介

酒精與癌症風險

酒精是什麼?

酒精又名乙醇,是一種存在於酒精飲料中的一種化學物質,如啤酒、蘋果酒、麥芽酒、葡萄酒和蒸餾酒(白酒)等酒精飲料。酒精是由酵母對糖和澱粉發酵而產生。某些藥品、漱口水和家用產品(包括香草精和其他的食品香精)中也含有酒精。本篇的內容著重於介紹飲用含酒精飲料與癌症的風險。

根據美國國家酒精濫用和中毒研究所 (National Institute on Alcohol and Alcoholism)的資料,在美國,一杯飲料的標準酒精含有14.0公克(0.6 盎司/18 毫升)的純酒精。換算來說,相同純酒精含量是各種酒精飲料是:

- 12盎司的啤酒 (355毫升的啤酒)

- 8-9盎司的麥芽酒 (237毫升-266毫升的啤酒)

- 5盎司的葡萄酒 (148毫升的葡萄酒)

- 1.5盎司(44毫升),或 "一份"80度的蒸餾酒精(酒)

公共衛生專家用這些含量制定有關飲酒的健康指南,並為人們提供一種比較飲酒含量的方法。然而,它們可能無法反映人們在日常生活中可能遇到的特有份量。

根據聯邦政府的2020-2025年美國人膳食指南,沒喝酒的人不應以任何理由開始喝酒。膳食指南還建議,喝酒的人要適度,男性每天飲酒不超過2杯,女性每天不超過1杯。大量飲酒的定義是:女性在任何一天喝4杯或以上,或每週喝8杯或以上;男性在任何一天喝5杯或以上,或每週喝15杯或以上。

NIAAA 將重度飲酒定義為:女性在任何一天喝酒4杯或以上,或每週喝酒8杯或以上;男性在任何一天喝酒5杯或以上,或每週喝15杯或以上。暴飲(binge drinking)則定義為:男性約2小時內喝酒5杯或以上、女性4杯或以上,請注意,所有暴飲的行為都是被認定為有害身體的。

近期,美國公共衛生部長發布的諮詢報告,呼籲應重新審視《美國人膳食指南》中關於酒精攝取量的建議上限,以面對酒精量達到或低於指南的量所導致罹癌風險增加的問題。

致癌風險

喝酒會致癌嗎?

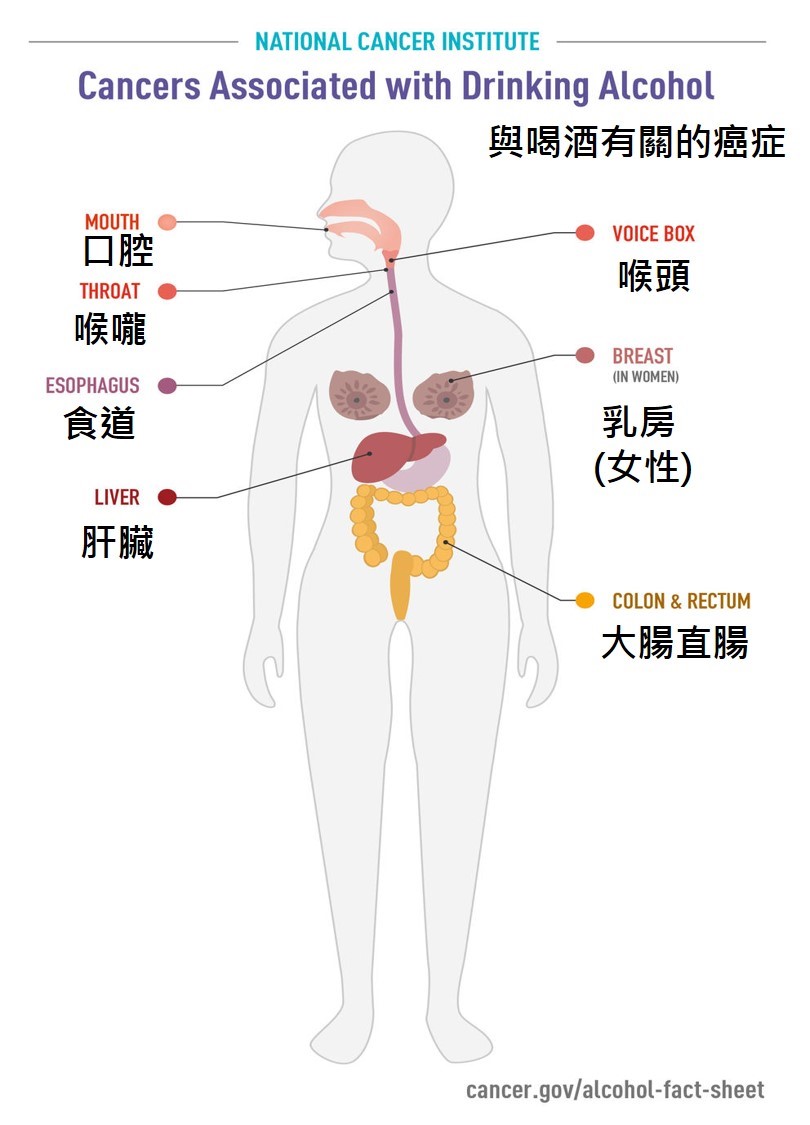

有強而有力的科學證據顯示喝酒會致癌(1, 2)。國際癌症研究機構(International Agency for Research on Cancer, IARC)早在1987年,就將酒精列為第一類致癌物(即對人類具致癌性的物質),因為有充分證據顯示酒精會導致人類口腔癌、咽喉癌、喉癌、食道癌及肝癌。美國國家毒理學計畫(National Toxicology Program)自2000年第九版《致癌物報告》中,已將酒精性飲料列為已知的人類有致癌物。根據流行病學研究顯示,與不喝酒的人相比,喝酒的人罹患某些癌症的風險較高,而且喝酒量越大,罹患這些癌症的風險就越高。然而,即使是輕度喝酒的人,也可能會增加罹癌風險。例如,每天只喝一杯酒的女性,其罹患乳癌的風險高於每週喝酒少於一杯的女性,若是重度喝酒或暴飲者,其風險則更高(3-7)。2019年,美國約180萬人診斷為癌症診斷,約有5%,將近10萬人與酒精攝取有關;同年約60萬例癌症死亡病例中,約有4%,近2萬5千人也與喝酒有關(8)。與不喝酒的人相比,喝酒的人會增加罹患以下癌症的風險:

*註:這些風險是相對風險,指的是一個群體(喝酒者)與另一個群體(不喝酒 者)相比,其新診斷罹患癌症的機率。但要注意的是,對於不常見的癌症( 例如,在美國,食道鱗狀細胞癌),即使相對風險很高,也可能只代表罹病 實際機率(即絕對風險)發生微小的變化。相反地,對於較常見的癌症,例 如乳癌,即使相對風險很小,也可能轉化為明顯增加的絕對風險。

| 癌症類別 | 喝酒會增加的風險* | 資料出處 |

|---|---|---|

| 口腔(嘴巴)和喉嚨 | 輕度喝酒者罹病風險可能高出1.8倍 重度喝酒者罹病風險可能高出5倍 |

4 |

| 聲帶 | 輕度喝酒者罹病風險可能高出1.4倍 重度喝酒者罹病風險可能高出2.6倍 |

4 |

| 食道(鱗狀細胞癌) | 輕度喝酒者罹病風險可能高出1.3倍 重度喝酒者罹病風險可能高出5倍 |

4 |

| 肝臟 | 重度喝酒者罹病風險可能高出2倍 | 4、9、10 |

| 乳房 | 輕度喝酒者罹病風險可能高出1.04倍 中度喝酒者罹病風險可能高出1.23倍 重度喝酒者罹病風險可能高出1.6倍 |

4、11、12 |

| 大腸直腸 | 中度至重度喝酒者罹病風險可能高出 1.2至1.5倍 |

4、11、13 |

*註:這些風險是相對風險,指的是一個群體(喝酒者)與另一個群體(不喝酒 者)相比,其新診斷罹患癌症的機率。但要注意的是,對於不常見的癌症( 例如,在美國,食道鱗狀細胞癌),即使相對風險很高,也可能只代表罹病 實際機率(即絕對風險)發生微小的變化。相反地,對於較常見的癌症,例 如乳癌,即使相對風險很小,也可能轉化為明顯增加的絕對風險。

延伸閱讀 :

危害證據

酒精如何產生致癌的風險?

使用澳洲的資料,並以美國的標準酒精飲料重新計算後,最近的美國公共衛生部長建議:

- 100位女性中,每週喝酒少於一杯的人,約有17人會罹患與酒精相關的癌症

- 100位女性中,每天喝一杯酒的人,約有19人會罹患與酒精相關的癌症

- 100位女性中,每天喝兩杯酒的人,約有22人會罹患與酒精相關的癌症

這表示,每天喝一杯酒的女性與每週飲酒少於一杯的女性相比,罹患酒精相關癌症的絕對風險增加了2%(每百人有2人),而每天喝兩杯酒的女性與每週飲酒少於一杯的女性相比,絕對風險增加了5%(每百人有5人)。於男性中,每週喝酒少於一杯者為每100人中有10人,每天喝一杯者為11人(每100人中增加1人),每天喝兩杯者為13人(每100人中增加3人)。

有些證據顯示,酒精攝取也可能增加罹患黑色素瘤、胰臟癌、攝護腺癌和胃癌的風險(4, 14)。然而,對於膀胱癌、卵巢癌與子宮癌,則未發現與飲用酒精有關,或目前證據並不一致。

多項研究也顯示,喝酒與腎臟癌(15–17)、甲狀腺癌(18, 19)及非何杰金氏淋巴瘤(20–22)的風險下降有關。然而,因喝酒而可能預防的這些癌症病例數,遠低於因喝酒所發生的癌症總病例數。

Q&A

酒精是如何致癌的?

研究人員提出了多種假說,說明酒精可能如何增加罹癌風(23),包括:

- 將酒精飲料中的乙醇代謝(分解)為乙醛,乙醛是一種有毒的化學物質,可能成為人類致癌物;乙醛會損害DNA與蛋白質

- 產生活性氧類(含氧的化學反應性分子),透過氧化作用破壞身內的DNA、蛋白質與脂肪

- 減弱身體分解與吸收與降低癌症風險有關的各種營養素的能力,包括維生素A、維生素B群(如葉酸)、維生素C、維生素D、維生素E與各種胡蘿蔔素

- 使口腔與喉嚨更容易吸收有害化學物質,例如香菸煙霧中的物質,進而導致癌症

- 增加血液中的雌激素濃度,它是一種高濃度的雌激素會導致乳癌

- 對單碳代謝與葉酸吸收有負面影響,會導致DNA損傷(24)

酒精和菸草併用會影響到癌症風險嗎?

流行病學研究顯示,與只使用酒精或菸草的人相比,同時使用酒精和菸草的人,其罹患口腔癌、口咽癌(喉嚨)、喉癌和食道癌的風險要高得多。事實上,對於口腔癌和口咽癌來說,同時使用酒精和煙草的風險造成的危害是倍增的;也就是說,併用的危害會比單獨使用酒精或菸草的大的多(25,26)。

人類的基因會影響酒精相關癌症的風險嗎?

個人罹患與酒精相關癌症的風險會受到他自己基因的影響,特別是轉換代謝(分解)酒精的相關酶類基因(27)。

例如,身體代謝酒精的一種方式是藉由一種稱為酒精去氫酶或ADH的酶的作用,該酶將乙醇轉換為致癌代謝物乙醛,主要在肝臟中進行代謝。近期的證據顯示,乙醛的產生也發生在口腔中,並可能受到口腔微生物群等因素影響(28, 29)。

許多東亞裔人中體內存在一種「超活性」的ADH,這種酶會加快速度將酒精(乙醇)轉換為有毒乙醛。於日本血統中,有這種超活性ADH的人,其罹患胰臟癌的風險高於擁有一般常見形式的ADH的人(30)。

另一種酶,稱為乙醛去氫酶2(aldehyde dehydrogenase 2, ALDH2),負責將有毒的乙醛代謝為無毒物質。有些人,特別是東亞裔,常帶有ALDH2基因的變異,造成在喝酒時導致乙醛累積。乙醛的累積會產生包括臉紅與心悸等令人不舒服的反應,因此大多數帶有ALDH2基因變異的人應少喝酒,如此他們罹患酒精相關癌症的風險也會較低。

然而,一些帶有ALDH2基因變異的人即使能容忍乙醛產生的不舒服反應,並喝酒量適中,也比帶有正常ALDH2酶的人,且攝取酒量差不多的人(31, 32),其罹患食道癌及頭頸部癌症的風險更高。這些風險增加的狀況,不會出現在帶有ALDH2基因變異但不喝酒的人身上。

什麼是酒精不耐症?

酒精不耐症(Alcohol Intolerance)是一種先天的基因缺陷,導致人體內缺乏乙醛去氫酶(Aldehyde Dehydrogenase, ALDH2),無法正常代謝酒精轉化成的乙醛。

一般來說,飲酒後的代謝途徑為身體將酒精(乙醇)轉化成乙醛,而乙醛去氫酶會再將乙醛代謝成無害的乙酸排出體外。然而酒精不耐症的人因為缺乏ALDH2,會使乙醛累積體內產生臉紅、頭痛、心悸、嘔吐等不適症狀。(註一)

喝酒會臉紅?喝酒臉紅又代表什麼?

喝酒臉紅是乙醛累積體內的一種現象,也是帶有酒精不耐症的人在飲酒後最常出現的徵狀,因為他們身體無法正常將乙醛代謝成乙酸。而喝酒臉紅的原因是因為乙醛會刺激微血管擴張,使血流量加大,導致臉部變紅,有些人甚至會全身通紅。(註一)

為什麼酒精不耐症議題對台灣人那麼重要?

因為台灣是所有亞洲國家中人民帶有酒精不耐症比例最高的國家! 而且在台灣許多人有「喝酒臉紅代表代謝好」這個錯誤觀念,但實際上喝酒會臉紅的人代表你的身體缺乏乙醛去氫酶,一點都不適合喝酒。(註一)

喝紅酒有助於預防癌症嗎?

用於釀造紅酒的葡萄和一些其他植物中,發現它們含有次級化合物白藜蘆醇,已用於研究包括預防癌症在內的多種潛在健康效益。然而,研究人員發現適量飲用紅酒與並不會增加罹患攝護腺癌 (33) 或大腸直腸癌 (33) 的風險。此外,近期一項綜合分析指出,喝紅酒或白酒與整體癌症風險之間並無差異(35)。

一個人停止喝酒後,罹患癌症的風險會發生怎樣的變化?

許多研究探討了一個人戒酒後癌症風險是否下降,結果顯示,停止喝酒後口腔癌、食道癌風險降低了,也可能咽喉癌、乳癌與大腸直腸癌的風險也會降低(36)。罹患癌症的風險可能需要數年才能恢復到與從不喝酒的人一樣,但停止飲酒永遠不嫌晚,罹癌風險仍能降低。

在接受癌症治療期間喝酒是否安全?

如同大多數與個別癌症治療有關的問題一樣,病人最好能詢問與他們的醫療團隊。負責治療的醫師與護理人員會告知治療期間或治療後是喝酒是否安全給出具體的建議,必須考慮的一點是:酒精可能會增加癌症復發或罹患第二種癌症的風險。

註一:台灣酒精不耐症衛教協會 Available at: http://www.taies.org/ALDH2/

文獻資料

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks toHumans. Alcohol consumption and ethyl carbamateExitDisclaimer. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of CarcinogenicRisks in Humans 2010; 96:3–1383.

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks toHumans. Personal habits and indoor combustions. Volume 100 E.A review of human carcinogens.Exit Disclaimer IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks in Humans 2012; 100(Pt E):373–472.

- Bagnardi V, Rota M, Botteri E, et al. Light alcohol drinking and cancer: a meta-analysis. Annals of Oncology 2013;24(2):301–308.

- Bagnardi V, Rota M, Botteri E, et al. Alcohol consumption and site-specific cancer risk: A comprehensive dose-response meta-analysis. British Journal of Cancer 2015; 112(3):580–593.

- Cao Y, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci EL. Light to moderate intake of alcohol, drinking patterns, and risk of cancer: Results from two prospective US cohort studies. BMJ 2015; 351:h4238.

- Chen WY, Rosner B, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, Willett WC. Moderate alcohol consumption during adult life, drinking patterns, and breast cancer risk. JAMA 2011; 306(17):1884–1890.

- White AJ, DeRoo LA, Weinberg CR, Sandler DP. Lifetime alcohol intake, binge drinking behaviors, and breast cancer risk. American Journal of Epidemiology 2017; 186(5):541–549.

- Islami F, Marlow EC, Thomson B, et al. Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(5):405-432.

- Grewal P, Viswanathen VA. Liver cancer and alcohol. Clinics in Liver Disease 2012; 16(4):839–850.

- Petrick JL, Campbell PT, Koshiol J, et al. Tobacco, alcohol use and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: The Liver Cancer Pooling Project. British Journal of Cancer 2018; 118(7):1005–1012.

- Esser MB, Sherk A, Liu Y, Henley SJ, Naimi TS. Reducing alcohol use to prevent cancer deaths: Estimated effects among U.S. adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2024;66(4):725–729.

- Sohi I, Rehm J, Saab M, et al. Alcoholic beverage consumption and female breast cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Alcohol, clinical &experimental research 2024; 48(12):2222–2241.

- Fedirko V, Tramacere I, Bagnardi V, et al. Alcohol drinking and colorectal cancer risk: An overall and dose-response meta-analysis of published studies. Annals of Oncology 2011;22(9):1958–1972.

- Zhao J, Stockwell T, Roemer A, Chikritzhs T. Is alcohol consumption a risk factor for prostate cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2016; 16(1):845.

- Mahabir S, Leitzmann MF, Virtanen MJ, et al. Prospective study of alcohol drinking and renal cell cancer risk in a cohort of Finnish male smokers. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 2005; 14(1):170–175.

- Rashidkhani B, Akesson A, Lindblad P, Wolk A. Alcohol consumption and risk of renal cell carcinoma: A prospective study of Swedish women. International Journal of Cancer 2005;117(5):848–853.

- Lee JE, Hunter DJ, Spiegelman D, et al. Alcohol intake and renal cell cancer in a pooled analysis of 12 prospective studies. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2007; 99(10):801–810.

- Peng G, Pan X, Ye Z, et al. Nongenetic risk factors for thyroidcancer: an umbrella review of evidence. Endocrine. 2025;88(1):60-74.

- Hong SH, Myung SK, Kim HS; Korean Meta-Analysis (KORMA) Study Group. Alcohol Intake and Risk of Thyroid Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Cancer Res Treat. 2017;49(2):534-547.

- Tramacere I, Pelucchi C, Bonifazi M, et al. Alcohol drinking and non-Hodgkin lymphoma risk: A systematic review and a meta- analysis. Annals of Oncology 2012; 23(11):2791–2798.

- Psaltopoulou T, Sergentanis TN, Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of hematological malignancies: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. International Journal of Cancer 2018; 143(3):486–495.

- Odutola MK, Nnakelu E, Giles GG, van Leeuwen MT, Vajdic CM. Lifestyle and risk of follicular lymphoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Cancer Causes & Control 2020; 31(11):979–1000.

- Rumgay H, Murphy N, Ferrari P, Soerjomataram I. Alcohol and Cancer: Epidemiology and Biological Mechanisms. Nutrients.2021;13(9):3173.

- Varela-Rey M, Woodhoo A, Martinez-Chantar ML, Mato JM, LuSC. Alcohol, DNA methylation, and cancer. Alcohol Res.2013;35(1):25-35.

- Hashibe M, Brennan P, Chuang SC, et al. Interaction betweentobacco and alcohol use and the risk of head and neck cancer:Pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck CancerEpidemiology Consortium. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers &

Prevention 2009; 18(2):541–550. - Turati F, Garavello W, Tramacere I, et al. A meta-analysis of alcohol drinking and oral and pharyngeal cancers: Results from subgroup analyses. Alcohol and Alcoholism 2013; 48(1):107–118.

- Druesne-Pecollo N, Tehard B, Mallet Y, et al. Alcohol and genetic polymorphisms: Effect on risk of alcohol-related cancer. Lancet Oncology 2009; 10(2):173–180.

- Stornetta A, Guidolin V, Balbo S. Alcohol-derived acetaldehyde exposure in the oral cavity. Cancers 2018; 10(1):20.

- Fan X, Peters BA, Jacobs EJ, et al. Drinking alcohol is associated with variation in the human oral microbiome in a large study of American adults. Microbiome 2018; 6(1):59.

- Kanda J, Matsuo K, Suzuki T, et al. Impact of alcohol consumption with polymorphisms in alcohol-metabolizing enzymes on pancreatic cancer risk in Japanese. Cancer Science 2009; 100(2):296–302.

- Yokoyama A, Omori T. Genetic polymorphisms of alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenases and risk for esophageal and head andneck cancers. Alcohol 2005; 35(3):175–185.

- Brooks PJ, Enoch MA, Goldman D, Li TK, Yokoyama A. The alcohol flushing response: an unrecognized risk factor for esophageal cancer from alcohol consumption. PLoS Med. 2009;6(3):e50.

- Vartolomei MD, Kimura S, Ferro M, et al. The impact of moderate wine consumption on the risk of developing prostate cancer. Clinical Epidemiology 2018; 10:431–444.

- Chao C, Haque R, Caan BJ, et al. Red wine consumption not associated with reduced risk of colorectal cancer. Nutrition and Cancer 2010; 62(6):849–855.

- Lim RK, Rhee J, Hoang M, Qureshi AA, Cho E. Consumption of Red Versus White Wine and Cancer Risk: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Nutrients. 2025;17(3):534.

- Gapstur SM, Bouvard V, Nethan ST, et al. The IARC Perspective on Alcohol Reduction or Cessation and Cancer Risk. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(26):2486-2494.

資料來源:“Alcohol and Cancer Risk was originally published by the National Cancer Institute.”

Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/alcohol/alcohol-fact-sheet馬偕紀念醫院耳鼻喉科 呂宜興醫師 協助校稿

更新日期:2025.05.12